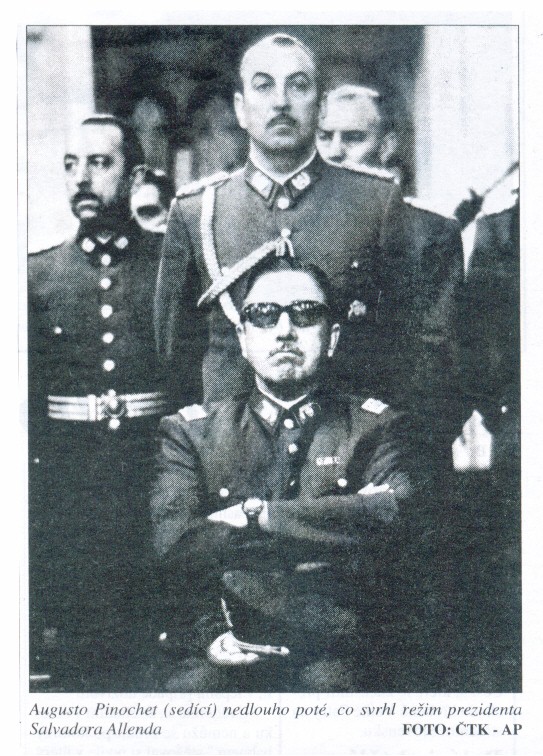

Pinochet, Chile’s former US-backed dictator, dead at 91

By Bill Van Auken

11 December 2006

News of the death of Chile’s former military dictator Augusto Pinochet sparked spontaneous demonstrations in Santiago and other Chilean cities Sunday.

Thousands poured into the streets or drove in horn-honking caravans to celebrate the death of the 91-year-old retired army general, who came to power in a 1973 CIA-backed coup against the elected government of Socialist Party President Salvador Allende.

Santiago’s La Alameda Bernardo O’Higgins, the capital’s principal thoroughfare, was filled with people chanting slogans and waving banners and signs. In working class suburbs of the capital—which were the scene during the dictatorship of brutal and indiscriminate repression—residents erected barricades and set bonfires to mark the death of the hated ex-ruler.

Pinochet’s regime was responsible for the murder or disappearance of thousands of left-wing activists, trade unionists, students and others suspected of opposing the interests of the Chilean ruling class and foreign capital. Hundreds of thousands of others were imprisoned, tortured and forced into exile under his dictatorship.

The popular joy provoked by the death of the aged state criminal was tempered considerably by the fact that he died in impunity, receiving intensive medical care in Santiago’s Military Hospital, rather than ending his days in a jail cell.

At the time of his death, Pinochet was facing some 300 criminal complaints related to the murder, torture and kidnappings carried out by his regime. “The Caravan of Death,” “Operation Colombo,” and “Operation Condor” were some of the murderous campaigns of repression for which he had been charged.

Both he and his family were also the object of criminal investigations related to the embezzlement of tens of millions of dollars in state funds that were funneled out of the country and into secret accounts at the Riggs Bank in Washington, DC, as well as other overseas financial institutions.

The evidence of shameless corruption on the part of the ex-dictator had in recent years diminished his support among a layer of the Chilean right, which had long justified his policies of mass murder and repression in the name of the “struggle against Marxism.”

Within the Chilean population, the latest trip to the hospital by the ex-dictator was viewed with extreme suspicion. It was widely seen as yet another ruse to escape criminal prosecution. Pinochet had been under house arrest before being admitted for treatment—the fifth time that a judge had imposed such confinement in recent years.

Meanwhile, at the military hospital where the ex-dictator died, a few hundred fascists and supporters of the military gathered, carrying portraits of Pinochet. Some of them carried out physical attacks on members of the press.

Internationally, there were also expressions of support for the ex-dictator. In Britain, former Tory Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher issued a statement declaring herself “greatly saddened” by the death of the indicated mass murderer.

Jack Straw, the Labourite leader in Britain’s House of Commons, issued a hypocritical statement declaring his hope that Pinochet’s death “will mean the Chilean people are able to move forward and put the legacy of those terrible years further behind them.”

It was Straw who, as Britain’s foreign secretary in 1998, issued an order allowing Pinochet to escape back to Chile after he had been held under house arrest in London for 503 days, while Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón sought his extradition to face trial for crimes against humanity. In the end, the government of Prime Minister Tony Blair protected the ex-dictator, invoking his ill health and “humanitarian” considerations.

In the US, the reaction to the former ally’s death was likewise characterized by extreme hypocrisy. The Bush White House issued a statement describing Pinochet’s dictatorship as “one of the most difficult periods in that nation’s history” and declaring that “our thoughts today are with the victims of his reign and their families.” Given the intimate ties of the US government—including leading officials in the present administration—with the crimes of the Chilean military regime, such statements are hardly credible.

Press reports on Pinochet’s death in many cases offered a “balanced” view of the ex-dictator’s legacy, lamenting his human rights record while praising him for “stabilizing” the Chilean economy and inaugurating the so-called “Chilean economic miracle.”

That the two processes are intimately related is not even hinted by these accounts. The “miracle,” reflected in high economic growth rates and the rise in stock values, was prepared precisely through a campaign of physical extermination against the most militant sections of Chilean workers, the outlawing of unions, the slashing of wages, and the elimination of all barriers to the ruthless exploitation of the working class.

The result was a vast transfer of social wealth from the working class majority to the financial aristocracy. According to statistics supplied by the Pinochet regime itself, between 1979 and 1989 the top 20 percent of the population increased its share of the national wealth from 51 percent to 60 percent.

Meanwhile, during the first 13 years of the dictatorship, the bottom 10 percent of Chilean society saw its overall consumption slashed by 30 percent. By 1988, the real wages of an average worker were 25 percent lower than they were in 1970.

The coup that brought Pinochet to power was launched on September 11, 1973. It saw Chilean Air Force combat planes bomb the La Moneda Palace, Chile’s White House, where Allende died.

The military junta headed by Pinochet disbanded Congress, banned political parties and trade unions and abolished freedom of speech and the right of habeas corpus.

Popular Unity’s disarming of the working class

The coup was facilitated by the policies of Allende’s popular front government itself, and particularly those of the Chilean Communist Party, which supported Allende. The Stalinist Communist Party worked to subordinate the intense revolutionary ferment within the Chilean working class to the popular front government. Allende and the Stalinists rejected demands to arm the workers and sought to break the wave of militancy that gave rise to factory occupations and land seizures.

The Stalinists and the Popular Unity government promoted unfounded and ultimately fatal illusions in Chilean parliamentary democracy, with the Stalinists describing the Chilean army as “the people in uniform.” It was Allende himself who brought generals into his cabinet and named Pinochet commander in chief of the Chilean armed forces, a position that Pinochet utilized to prepare and execute the coup that ended the Socialist Party president’s life.

In the days that followed the coup, tens of thousands were rounded up, many of them herded into Santiago’s football stadium, where most were beaten and tortured and many were executed. Among those murdered were two US citizens, Frank Teruggi and Charles Horman. Subsequent evidence has indicated that senior US officials not only worked to cover up the crime, but were complicit in these killings.

The coup itself enjoyed the full sponsorship of the administration of President Richard Nixon. Millions of dollars were covertly sent into Chile by the CIA to finance employers’ strikes and fund fascist groups seeking Allende’s overthrow. Nixon’s explicit order to the CIA was to “make the economy scream” in order to bring down the government. The plans of the military coup plotters were shared and coordinated fully with both the CIA and the Pentagon.

Henry Kissinger, then Richard Nixon’s national security advisor—and today a key advisor to the Bush administration—was the principal American architect of the coup in Chile. In 1970, when Allende’s Popular Unity government was first elected, Kissinger commented, “I don’t see why we need to stand idly by and let a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”

The US government subsequently set out to reverse the results of this popular election by means of covert subversion, terror and military force.

While Pinochet is dead, Kissinger still lives and is liable for criminal prosecution for his role in fomenting a coup that claimed the lives of thousands.

Nor is he the only US official complicit in the crimes of the Pinochet dictatorship. George H.W. Bush, the former US president and current president’s father, was CIA director during the period in which Pinochet’s regime served as the axis for “Operation Condor,” a coordinated campaign of murder and repression carried out by military regimes throughout Latin America against left-wing opponents.

Declassified US documents have proven that the CIA was kept fully informed of this operation, in which hundreds if not thousands were murdered or illegally imprisoned and tortured.

Part of the operation included what was at the time the worst act of international terrorism ever carried out on US soil. On September 21, 1976, a car bomb took the life of Orlando Letelier, Allende’s former foreign minister and a prominent opponent of the Pinochet regime, as well as that of his American aide, Ronni Moffit, as they were riding through the streets of Washington, DC.

The CIA, under Bush senior’s leadership, worked to cover up the Pinochet regime’s responsibility for these murders. The killers themselves were subsequently placed under US protection and given new identities and financial support under the federal witness protection program.

Vice President Dick Cheney and outgoing Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld are likewise implicated in Washington’s support for the Pinochet dictatorship during this period. Cheney was the White House chief of staff and Rumsfeld was also defense secretary then, overseeing US ties to the Latin American military as Operation Condor was unfolding.

Pinochet’s ability to escape prosecution until his death at the ripe old age of 91—more than 16 years after surrendering power—is testimony to the fact that the horrors his regime unleashed against the workers of Chile were carried out to defend the interests of the ruling elite both in that country and internationally, which continued to protect him.

This protection also constitutes a serious warning. The brutal methods of mass murder, torture and dictatorship that will forever be associated with the name of Augusto Pinochet remain the ultimate recourse of capitalism in crisis.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home